April 4, 2023

A Tale of Two Princes

The U.S. Supreme Court should issue a ruling soon in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith. This is the latest Supreme Court case to examine copyright law and the doctrine of fair use which, together, are supposed to both encourage the creation of art by ensuring creators own (and are paid for) their work while also allowing others to use existing works to create new ones. The stakes are high because the potential creative and financial ramifications are huge.

Following up on the previous blog post: how did it all come to this?

The most straightforward answer is that we got here by judges (trying) to make principled decisions about when borrowing is fair use and when it’s infringement. With visual art, to put it mildly, this is tricky.

By way of example, according to the Second Circuit, this:

is fair use of these:

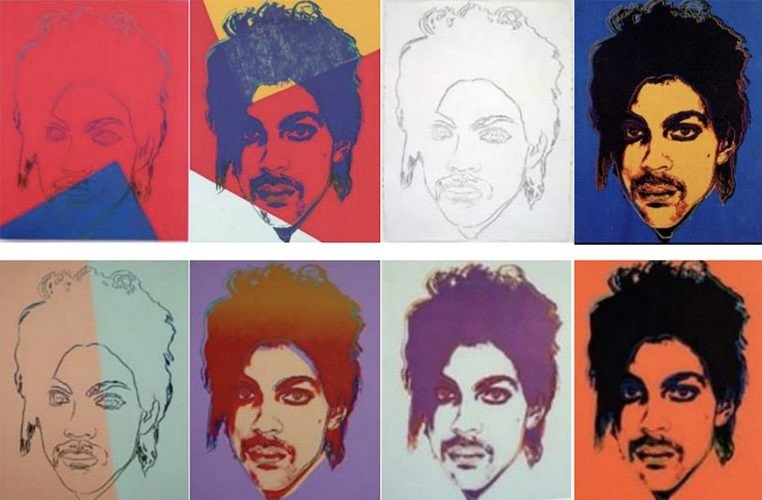

but, these:

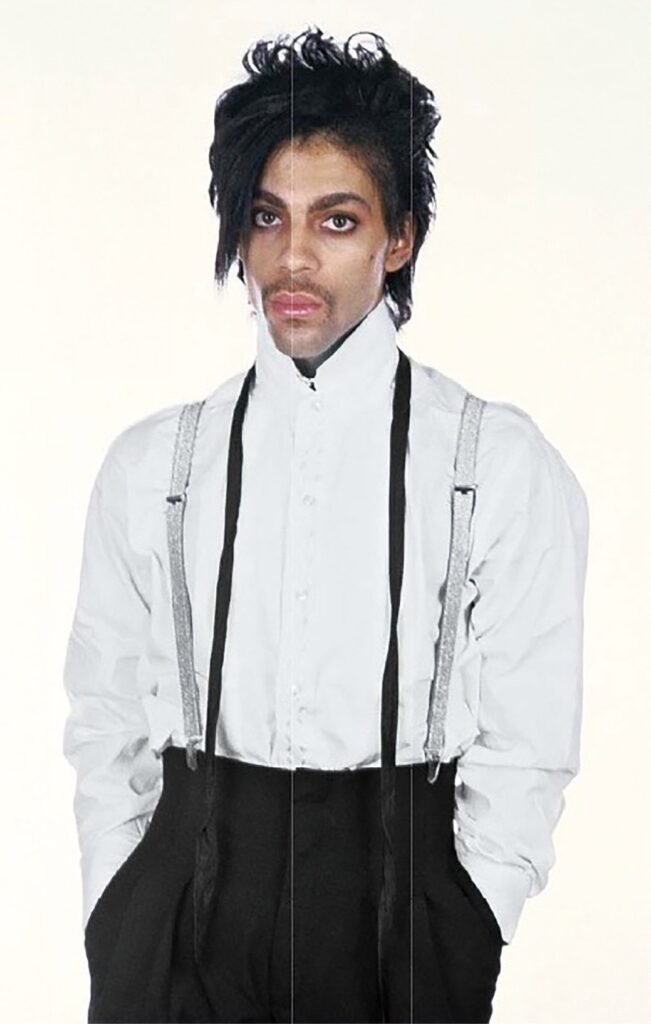

which incorporate this,

are not.

The first set of images comes from Cariou v. Prince, a case in which photographer Patrick Cariou sued “appropriation” artist Richard Prince over 30 artworks Prince created that included elements of Cariou’s photos of Rastafarians. The Southern District of New York ruled in favor of Cariou, holding that Prince’s works were not fair use because they didn’t comment on or criticize Cariou’s photos.

The Second Circuit disagreed. It found that the District Court imposed an incorrect legal standard by requiring Prince’s work to comment on Cariou’s work.

Instead, the Second Circuit emphasized that to constitute fair use, the later work must “alter the original with “new expression, meaning or message.” The Second Circuit took this standard from a 1994 Supreme Court case, Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., which involved 2 Live Crew’s adaptation of Roy Orbison’s song “Pretty Woman.” In particular, the Second Circuit held that Prince’s artworks had an “entirely different aesthetic from Cariou’s photographs.” Based on this, the Second Circuit concluded that 25 of Prince’s artworks were sufficiently transformative to constitute fair use (the question of the remaining five works was remanded to the District Court).

In reaching this conclusion, the Second Circuit said that it shouldn’t be read to suggest that any cosmetic changes are enough to mean that something is fair use. Rather, it emphasized the fact that Prince’s images had “a fundamentally different aesthetic” than Cariou’s photos.

While that certainly appears to be true in Cariou, it also may be true in Warhol v. Goldsmith — as the Warhol Foundation has argued — that the Prince Series has a very different aesthetic from Goldsmith’s portrait of Prince. But how do artists (or lawyers or judges) determine how much transformation is enough to put them in the clear? Is it possible to predict how a court will balance the elements that go into a fair use analysis? Is there a way to define or measure exactly how much of a different aesthetic is required? Moreover, when is a secondary use “derivative,” meaning that the original owner controls the right to make additional works, and when is it fair use?

More on this next time.