October 8, 2024

Over the last few years there have been several cases of professional models suing “gentlemen’s clubs” (a/k/a strip clubs) for defamation. These suits involve the clubs grabbing the models’ pics off the Internet and using them on social media to promote their entertainment. (Weirdly, all of these suits are against strip clubs in New England. Draw your own conclusions.) None of this is particularly surprising. However, one current case has raised the interesting question of when the statute of limitations begins to run on defamation claims stemming from social media posts.

In this case, five models are suing Club Alex in Stoughton, Massachusetts, alleging the club used their photos in Facebook posts, creating the impression the models worked as dancers there. That’s defamation!

The club pushed back, noting that the offending posts were made between 2013 and 2015, but the models didn’t bring the lawsuit until 2021 — well after the three-year statute of limitations for defamation claims in Massachusetts had expired. On those grounds, the federal Court hearing the case initially granted the club’s motion to dismiss.

The models asked the Court to reconsider that decision. And, amazingly, the Court did!

Why would a federal judge basically admit, “ok, maybe I was wrong”? In a nutshell, here’s why: In some cases, Massachusetts (and most other states) use a “discovery rule” to determine when the statute of limitations starts to run. This avoids the unfairness of having statutes of limitations expire before a “Plaintiff knew or reasonably should have known that she may have been harmed by the conduct of another.” The models argued that this should also apply here because the vast ocean of information on social media meant they didn’t know (and couldn’t be reasonably expected to know) about the misappropriation of their images until years after the posts. What’s more, even if they had suspected misuse of the images, it’s very difficult to manually search thousands of strip clubs’ social media pages and websites, especially when search engines can’t search images without names.

Recognizing the models’ point, the District Court sent the issue to the Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) of Massachusetts — the highest state Court in that state — asking “under what circumstances, if any, is material publicly posted to social media platforms ‘inherently unknowable’ for purposes of applying the discovery rule in the context of defamation, right of publicity, right to privacy and related tort claims?”

The SJC held that, in the context of social media posts, a determination of when the statute of limitations begins to run should not be based on the date of publication, but rather “requires a fact-intensive, totality of the circumstances analysis to determine what the Plaintiff knew or should have known about the social media publication.” (It noted that this is not required where postings are widely available and readily searchable).

The SJC instructed judges faced with this issue to consider things like: “how widespread the distribution was;” whether the posting could be readily located by a search; if there is technology that could assist in locating potentially offending posts; and how widely the images are distributed and, thus, how hard or easy it is to separate authorized uses from unauthorized uses.

Here, this means that the models can continue to pursue their defamation claims against the club.

A final thought: In a way, this is the flipside of the Netflix case involving their series Baby Reindeer and the lawsuit against them by Fiona Harvey, which I wrote about here. In that case, the information on social media enabled Internet sleuths to out someone whose identity was meant to be concealed, whereas in this case, the volume of information on social media makes it more difficult to find out when someone’s persona is being used without their knowledge. Whichever way you look at it, one thing is certain: Controlling our identities (and our lives) is waaay harder than it used to be.

September 24, 2024

Almost two years ago, I wrote about LinkedIn’s suit against hiQ Labs, Inc. In that case, LinkedIn sued hiQ Labs for scraping its users’ public profiles and selling the results as part of an employee training and retention tool. There, the Court found that hiQ Labs violated the social media company’s terms of service because, as it states very clearly in LinkedIn’s user agreement, “NO SCRAPING.” (I’m paraphrasing, loudly.)

We now have a second court decision ruling against scraping — but for a very different reason than in the hiQ action.

This time, the venue is the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals and it’s that court’s second decision in the case since the dispute began in 2016. In its first decision (back in 2020) the 11th Circuit wrote: “Warning: This gets pretty dense (and difficult) pretty quickly.” That’s true! But don’t be scared. I think we can summarize it all succinctly without getting lost.

The plaintiff is Compulife Software, Inc., whose products are a database and software that allows licensees (generally, insurance agents) to compare life insurance quotes. These agents/licensees can incorporate Compulife’s products into their websites, but the public can also access Compulife’s products on its own site, www.term4sale.com.

The defendants are a group of individuals who used bots to scrape Compulife’s publicly-accessible site and database and built their own, competing insurance quote site. This group (they never actually formed a business entity) obtained the source code for Compulife’s software under false pretenses. (One of the group’s members contacted Compulife, claiming that he worked for one of Compulife’s licensees, and asked for a copy of the source code. Compulife gave it to him.) The defendants’ used this code to engineer the scraping of Compulife’s website.

Based on this, Compulife accused the defendants of violating the federal Defend Trade Secrets Act, as well as the analogous Florida Uniform Trade Secrets Act. (There were also copyright infringement claims relating to defendants’ unauthorized use of Compulife’s software, but that’s for another day). To prevail on either claim, Compulife had to establish that (1) it had a trade secret, and (2) the defendants misappropriated Compulife’s trade secret.

Initially, the District Court held that Compulife didn’t have a protectable trade secret because its entire database could be accessed by the public. However, in its 2020 decision, the Appeals Court reversed this, concluding the database was indeed a trade secret because, among other things, Compulife “goes to great lengths to secure its database” and that even though the individual, publicly-available quotes on the Compulife site were not trade secrets, Compulife’s compilation of them could be.

On this latest appeal, the main issue was whether the defendants’ use of bots to scrape Compulife’s database was misappropriation. The 11th Circuit, in addition to reaffirming its original holding that Compulife’s database was a trade secret, concluded that defendants misappropriated that secret when they used bots to “commit a scraping attack that acquired millions of variable-dependent insurance quotes.” That quantity was a key factor: As the Court wrote, “even if individual quotes that are publicly available lack trade secret status, the whole compilation of them (which would be nearly impossible for a human to obtain through the website without scraping) can still be a trade secret,” and the defendants’ use of bots to do what a human could not manually accomplish represented improper means.

The Appeals Court, however, was careful not to condemn scraping as a whole, writing “[i]t is important to note that scraping and related technologies (like crawling) may be perfectly legitimate.” (Italics from the court’s opinion).

This seems pretty straightforward particularly given defendants’ acquisition of Compulife’s code under false pretenses. However, I’m curious to see future rulings that shed more light on when scraping is legitimate and, more importantly, what factors do courts look at to determine when scraping is ok and when it’s not? Is it the sheer volume of material taken? The impact on the plaintiff’s business? Something else?

When the 11th Circuit (or another court) enlightens us, I’m sure I’ll be back to write about it.

September 9, 2024

Last week, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed a federal judge’s March 2023 holding that the Internet Archive’s practice of digitizing library books and making them freely available to readers on a strict one-to-one ratio was not fair use. For reasons I’ll get into below, the outcome is pretty unsurprising. It’s also worth looking at because it likely previews some of the arguments we’ll hear in the case between the New York Times and OpenAI (creators of ChatGPT) and Microsoft if (or when) that case makes it to the Second Circuit. (Quick summary of my post on the subject: The New York Times Company filed suit late in December against Microsoft and several OpenAI affiliates, alleging that by using New York Times content to train its algorithms, the defendants infringed on the media giant’s copyrights, among other things.)

First, some background. The Internet Archive is a not-for-profit organization “building a digital library of Internet sites and other cultural artifacts in digital form” whose “mission is to provide Universal Access to All Knowledge.” To achieve this rather lofty goal, the Archive created its Open Library by scanning printed books in its possession or in the possession of a partner library and lending out one digital copy of a physical book at a time, in a system it dubs Controlled Digital Lending.

Enter COVID-19. During the height of the pandemic, when everyone was stuck at home without much to do, the Archive launched the National Emergency Library. This did away with Controlled Digital Lending and allowed almost unlimited access to each digitized book in its collection.

Not surprisingly, book publishers, who sell electronic copies of books to both individuals and libraries, were not thrilled. Four big-time publishers — Hachette, Penguin Random House, Wiley, and HarperCollins — sued the Internet Archive for copyright infringement, targeting both its National Emergency Library and Open Library as “willful digital piracy on an industrial scale.”

The Internet Archive responded that these projects constituted fair use and, therefore, did not infringe on the publisher’s copyrights. To back this up, the Archive claimed it was using technology “to make lending more convenient and efficient” because its work allowed users to do things that were not possible with physical books, such as permitting “authors writing online articles [to] link directly to” a digital book in the Archive’s library. The Archive also insisted its library was not supplanting the market for the publisher’s products.

The District Court rejected these arguments, holding that no case or legal principle supported the Archive’s defense that “lawfully acquiring a copyrighted print book entitles the recipient to make an unauthorized copy and distribute it in place of the print book, so long as it does not simultaneously lend the print book.” The judge also deemed the concept of Controlled Digital Lending “an invented paradigm that is well outside of copyright law.”

In affirming the District Court’s ruling, the Second Circuit Court applied the four-part test for fair use that looks at: (1) the purpose and character of the use; (2) the nature of the copyright work; (3) the portion of the copyrighted work used (as compared to the entirety of the copyrighted work); and (4) the impact of the allegedly fair use on the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The first factor — the purpose and character of the use — is broken down into two subsidiary questions: Does the new work transform the original, and is it of a commercial nature or is it for educational purposes? Neither the District Court nor the Court of Appeals bought the Internet Archive’s claim that its Open Library was transformative. The Court of Appeals held that the digital books provided by the Internet Archive “serve the same exact purpose as the original; making the authors’ works available to read.” (The Court of Appeals did find that, as a not-for-profit entity, the Internet Archive’s use of the books was not commercial.)

On the second factor, which is generally unimportant here, the Court of Appeals also found in favor of the publishers. Of greater significance is factor three, which looks at how much of the copyrighted work is at issue. Copying a sentence or a paragraph of a book length work is more likely to be fair use than copying the entire book which, of course, is exactly what the Internet Archive was doing. Again, another win for the publishers.

And arguments on factor four — the impact on the market for the publishers’ products — didn’t work out any better for the Internet Archive. Notably, the Court of Appeals found that the Internet Archive was copying the publishers’ books for the exact same purpose as the original works offered by the publisher, thus naturally impacting their market and value.

So what are the takeaways here as we look ahead to the case between the New York Times and Open AI/Microsoft?

On the one hand, OpenAI/Microsoft have copied entire articles from the Times (and the numerous other plaintiffs that are suing OpenAI and Microsoft), which will hurt OpenAI/Microsoft claims of fair use. Likewise, OpenAI/Microsoft’s fair use arguments won’t get very far if the Times can show that ChatGPT’s works are negatively impacting the market for its work or functioning as a substitute for journalism.

On the other hand, if OpenAI/Microsoft can show that ChatGPT’s output transformed the Times’ content, it may be able to prevail on fair use.

In any event, the case between OpenAI and Microsoft and The New York Times is likely to include a lot more ambiguity than in the Internet Archive matter, with the potential to result in new interpretations of copyright law with massive consequences for media and technology companies worldwide.

August 26, 2024

I spend a lot of time here nerding out about interesting cases and the many provocative types of legal conflict that continually arise. Keeping up with trending issues is an important part of what I do, and the latest disputes are more fascinating than ever.

But there’s another big part of my job that I talk about less that is just as captivating: Working with clients.

Why do I generally keep mum about this? Obviously, I can’t reveal any privileged client information. Also, litigation can be stressful, clients can sometimes have meltdowns and throw tantrums, and I’m not going to write about people’s bad moments even if they might be instructive for others. Finally, unlike reading and interpreting statutes and cases, working with clients isn’t something I learned in law school. It is a skill gradually acquired over years of practice and continual improvement. As a result, I (and most other lawyers I know) don’t really have an academic framework to organize and disseminate my expertise about working with clients.

But fear not: I’ve got a few things to share. Specifically, emotions, beliefs and behaviors I’ve seen that cause clients (and attorneys) needless stress and can make it harder to produce good results. Recognizing and anticipating these problem areas can help clients and attorneys have much better experiences as they navigate difficult litigation. (Also, it never hurts for me to put my thoughts down so that I can come back to them. Everybody wins!)

- The “It’s not fair!” syndrome. I think that a lot of people come to me feeling they’ve been treated in a way that is unfair and they expect “the law” to be on their side, and for lawyers and courts to make things right. In an ideal world that is exactly what would happen but, alas, as should be obvious to anyone over the age of 4, we don’t live in an ideal world. “The law” is made up of people. People with wildly differing beliefs and agendas. People who sometimes just plain get things wrong (that’s why we have appellate courts). Moreover, what’s fair to one person might not be fair to someone else. It’s important people put aside that powerful “it’s not fair!” feeling and focus instead on getting attainable, satisfactory results.

- “And another thing!” A lot of times people are determined to tell the opposite side in a dispute everything they’ve done wrong. But, in my experience, not every little thing matters. It is better to have one or two really good examples of why you’re right and/or the other side is wrong rather than throw everything but the kitchen sink at them. Doing so cuts down on needless back and forth and keeps the focus on those points that have power to change the situation. Plus, keeping some weapons in your arsenal in case you need them later is always a good idea.

- “Same thing, same result.” Often, when people come to me, they’ve already spent a lot of time going back and forth with their adversary and discussions have fallen into a predictable pattern. For example, your side keeps asking for information and the other side keeps ignoring these requests. And on and on. If you keep doing the same thing, you’ll probably keep getting the same result. That’s frustrating. If you want something different to happen, clients and attorneys need to be willing to try something different.

- “I’m not going to tell you.” If you’re a client, err on the side of telling your attorney too much, not too little. I cannot stress this enough. It’s much harder for me to help you solve a problem if I don’t have all the relevant information about the dispute, the opponent, and yourself. Anything can come up in a case, and the more unexpected it is, the more detrimental it can be — and the more stressful for my clients and myself. If I know about it, I can anticipate and plan for it.

- Finally, it’s important to draw lines (I’m not going to say, “in the sand!”). When you’re making demands of your adversary or laying out expected results, set boundaries and stick with them (of course, always be willing to adjust if you receive new information). If you don’t enforce a boundary, it can be a lot harder to get the other side to believe that this time you really mean it. When a client panics and suddenly wants to cave in on something their attorney doesn’t want to budge on, it causes tension between the two of you and jeopardizes your negotiating power going forward.

In all this, there’s a difference between understanding potential behaviors and eliminating them. But recognizing these patterns is definitely a productive first step toward ensuring a smoother, less stressful process for everyone involved in a litigation.

August 6, 2024

Everything should be clicking (as it were) for TikTok influencer Sydney Nicole Gifford. She has half a million followers who eat up her posts promoting home and fashion items from Amazon, propelling her to the kind of celebrity that garnered coverage in People for her pregnancy. But alas, Gifford is apparently a little too influential.

She claims fellow TikToker Alyssa Sheil is copying her posts and using Gifford’s visual style to promote the same products! And yes, Gifford is now suing Sheil, in a case that could shake up the world of social media influencers and potentially make it harder for influencers to create content without fear of accusations of copying.

According to the complaint, which was filed in District Court in Texas, Gifford “spends upwards of ten hours a day, seven days a week, researching unique products and services that may fit her brand identity, testing and assessing those products and services, styling photos and videos promoting such products and editing posts…” for social media. As a result, according to the complaint, “Sydney has become well-known for promoting certain goods from Amazon, including household goods, apparel, and accessories, through original photo and video works…”

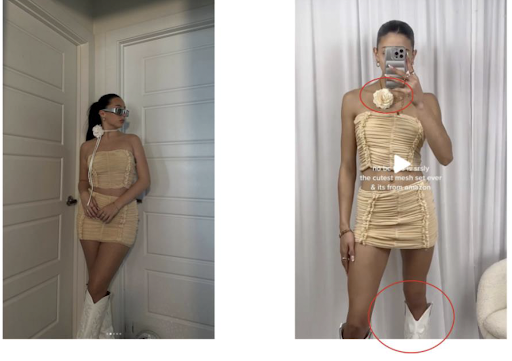

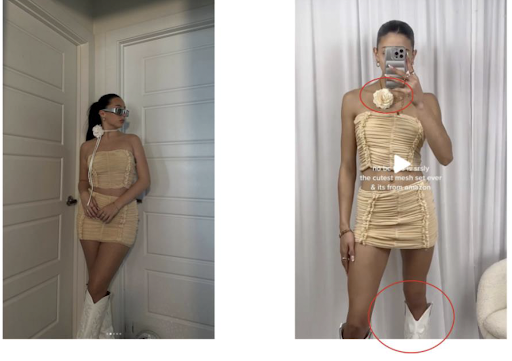

The lawsuit goes on to allege that defendant Sheil “replicated the neutral, beige, and cream aesthetic of [Gifford’s] brand identity, featured the same or substantially [the same] Amazon products promoted by [Gifford], and contained styling and textual captions replicating those of [Gifford’s] posts.” It says at least 40 of Sheil’s posts feature “identical styling, tone, camera angle and/or text,” to Sydney’s. Here’s a pretty obvious one, with Gifford on the left and Sheil on the right.

In the suit, Gifford is claiming, among other things, trade dress infringement, violation of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, copyright infringement (she has registered copyrights for some of her posts and videos), and unfair competition.

Does Gifford have a case? Here’s what I think:

- To prevail on the claim for infringement of her trade dress Gifford will have to establish, at a minimum, that consumers associate her “aesthetic” with her. That may be difficult because, at least to my eye, the style of Gifford’s posts doesn’t seem wildly different from a lot of other influencers. (I am so not her target audience and I’m doing my best not to dunk on her “aesthetic,” but I have to put “aesthetic” in quotes to convey my eyeroll.)

- The claim under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act is based on the fact that Sheil removed Gifford’s name or social media handle from posts. This is, shall we say, a novel argument given that the intent of the DMCA is to prevent people from circumventing digital rights management software. This is not that. At all.

- The copyright claim is going to raise a lot of questions about exactly how original these social media posts are and, as a result, how much protection under copyright law they are entitled to. Gifford and other social media influencers might find out that they don’t like the answer to this question.

- If Gifford is able to establish that consumers associate her “aesthetic” with her, she could win the battle… but lose the war because it might open her up to lawsuits by other influencers who claim that she copied their look.

Meanwhile, Sheil has asked the Court to dismiss Gifford’s case.

Thinking more broadly, a decision or decisions on the copyright claim could have implications for appropriation artists and others who closely copy another creator’s work. Which is one reason it will be fascinating to see how this plays out. And yes, I know I often end these posts saying something like that. Because it’s true! This case, as with so many IP lawsuits lately, especially those that involve AI, are all going where no court has gone before (or even imagined possible ten years ago). Every one of these potential decisions could have massive socioeconomic impact, with a real effect on how a lot of people earn a living and how the rest of us spend a lot (probably too much) of our time.

July 23, 2024

What do Baby Reindeer and Inventing Anna have in common? Sure, both are miniseries on Netflix. More interestingly, though, and more pertinent to this blog (since I’m not Roger Ebert), both are subjects of defamation lawsuits against the streaming giant. Nor is either action the first; I previously wrote about Linda Fairstein’s defamation lawsuit against Netflix over how she was portrayed in When They See Us. (That case settled in early June.)

These two current cases touch on slightly different aspects of defamation law. Inventing Anna tells the “based on a true story” of con artist Anna Sorokin, who posed as an heiress and defrauded a variety of New York institutions and individuals out of somewhere around $275,000. In addition to the protagonist, the series portrays several of her real life friends, including Rachel DeLoache Williams, the plaintiff in the lawsuit. Williams claims the series’ version of her is false and defamatory, especially in scenes showing her character abandoning a depressed Sorokin in Morocco and thus painting her as a “disloyal” and “dishonest” villain (instead of a victim who was defrauded by Sorokin to the tune of $62K).

Netflix sought to dismiss the lawsuit on grounds the allegedly defamatory statements were substantially true or were not defamatory. It argued that the show’s creators have a “literary license” to give their interpretation of events, and the characterization of Williams was an opinion, protected by the First Amendment from defamation claims.

The District Court did not see things this way and in March of this year it denied the motion finding that, at the very least, some portions of Netflix’s portrayal of Williams were false and capable of a defamatory interpretation. Specifically, the Court concluded that the issue of whether Sorokin was actually distraught in Morocco, or if that was an invention of the producers, is a question of fact that can be proven true or false. (To oversimplify things a bit, only false statements of fact can serve as a basis for a claim of defamation.) “Whether Sorokin was in a troubled state and Williams left her at that point can be proven true or false,” the judge wrote. The Court further concluded that showing the Williams character ditching a friend when she was depressed could indeed leave viewers with a negative view of the real Williams, and thus serve as the basis for a defamation claim. The case is proceeding.

In contrast, the Baby Reindeer case will focus on the question of whether the series’ portrayal of the character Martha is “of and concerning” a real-life person — the plaintiff, Fiona Harvey.

Baby Reindeer, which begins with the words “this is a true story,” was written by Richard Gadd, who also plays central character Donny Dunn, a not very funny wannabe comedian. It’s a fictionalized version of Gadd’s own life, and part of Donny’s saga involves being stalked by a character named Martha, which Gadd drew off a real experience.

According to the lawsuit, filed in early June, Harvey claims Gadd based Martha on her and cites several similarities between real life and fiction, including that both Martha and Harvey are Scottish lawyers of about the same age who live in London. The suit also claims that Harvey bears an “uncanny resemblance to ‘Martha’” (or at least the actress who plays the character), and “‘Martha’s’ accent, manner of speaking and cadence, is indistinguishable . . .” from Harvey’s.

Moreover, one plot point in Baby Reindeer (I’m trying to avoid spoilers as the show has a lot of twists and turns that would sound ridiculous if you haven’t watched it) mirrors something that Harvey tweeted at Gadd in 2014. Because of these similarities, according to the Complaint, within days of the series airing Internet sleuths determined she was the basis for Martha and began subjecting her to social media vitriol. “As a result of [Netflix’s] lies, malfeasance and utterly reckless misconduct, Harvey’s life had been ruined,” the suit states.

Harvey claims she was defamed by Netflix because Baby Reindeer portrays Martha as “a twice convicted criminal” who spent five years in prison for stalking people, as well as physically and sexually assaulting Donny. Harvey says she has never been convicted of any crime and did not attack the real-life Gadd.

The interesting issue here is that relevant case law doesn’t include, as a test, whether a fictional character can have their real-life basis be identified by Internet sleuths. Rather, the inquiry is generally whether a person who knows the plaintiff would reasonably conclude that the plaintiff was the fictional character, or in this case, whether friends and acquaintances of Harvey would link her with Martha. Netflix has been pretty adamant that it took steps to disguise the identity of the real Martha. Since there are numerous elements in the Martha character’s storyline that are clearly not connected to anything in Harvey’s real life, it seems very possible that the real Martha is someone other than Harvey. But the Internet has spoken, and that’s enough for Harvey to sue Netflix for $170 million.

We’ll have to see how all this pans out; it should make for pretty good legal viewing (although nowhere near as popular as Baby Reindeer itself, which is set to become Netflix’s most-streamed show ever).

One final note: Some people have asked me if I think there’s something wrong with Netflix’s legal vetting of shows. The answer: maybe, but let’s keep in mind that Netflix produces A LOT OF CONTENT, and obviously most of it isn’t causing trouble. That said, it seems like the streaming behemoth should start to exercise a bit more caution when greenlighting these series based on real stories, because there is a lot of money at stake, the Internet is rife with people looking to dig up the “truth,” and someone, somewhere, may very well cry defamation.

July 10, 2024

I’m a litigator (you probably know that). I’m also a mom to a tween (that might be new information!). Both are generally very rewarding, but can also sometimes be a huge PITA.

They go together much better than you might expect because, oddly enough, I’ve found that some of the things I’ve learned as a parent make me a better lawyer and vice versa.

Because I had a few days off for Independence Day last week, I was able to spend some much-needed time with my family, along with some friends and their two-year-old. And during those languid summer days of leisure I was able to reflect on the overlap between practicing law and raising a kid.

A few highlights:

- Sometimes you just have to wait it out. Toddlers and tweens have their angry, stubborn and argumentative moods, and often nothing you say or do is going to get them out of one. Trying can even make it worse. This is also true for adversaries, clients, and judges. Sometimes people just need a beat or two to come around on their thinking, and your actions aren’t going to get a child, an adversary, a client or a judge to where you want them to be any faster. Sometimes the best approach is to simply say your piece briefly and then be quiet.

- Just because someone is loud, it doesn’t mean you have to give in to their demands or be loud back. As in point number one above, sometimes the child’s moods come with a lot of screaming or yelling. Same with clients and adversaries. It doesn’t help to respond in kind. More often than not, at least for me, the best approach is to keep on doing what I’m doing and not let all the noise change my path toward the end goal.

- However, listening is important. While #1 and #2 can be crucial, never completely tune out what’s being said. Sometimes in the midst of a person’s screaming fit, they’ll say some little pearl that highlights what’s really motivating the outburst (in the case of a tween) or a sticking point (in the case of an adversary). It’s important to be present, listen for those moments and store them away in case they prove useful down the line.

Of course, when it comes to a child, you know that someday, somehow, EVENTUALLY they’ll grow up and act like adults. I’m not going to comment on some adversaries.

June 25, 2024

The web is rife with articles explaining the importance of protecting a business’s trademarks. Some of them are even on this blog!

These articles usually (and correctly) point out that if someone is potentially infringing on your business’s trademark, it’s important to send a cease and desist letter or, if necessary, file a lawsuit because if others start to use your mark (or something like it) and the business doesn’t protect it, you can eventually lose trademark protection.

However, sometimes, it might be better not to start the legal ball rolling. I say this even though I’m a litigator, and yes, one of the ways I earn my living is by helping businesses sue for trademark infringement. Why? A couple of recent cases highlight the importance of taking a step back and thinking things through before sending that cease and desist letter or filing a lawsuit.

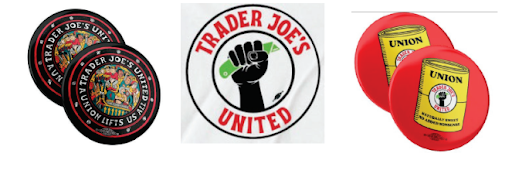

For starters, Trader Joe’s case against its employee union, Trader Joe’s United. The union sells mugs, tee shirts, and other merch branded with their Trader Joe’s United logo to raise money for organizing locations throughout the supermarket chain. Trader Joe’s claimed trademark infringement and sued. For comparison, here are Trader Joe’s marks:

And here’s what the union used:

The District Court granted the union’s motion, writing that it felt “compelled to put legal formalisms to one side and point out the obvious. This action is undoubtedly related to an existing labor dispute. It strains credulity to believe that the present lawsuit — which itself comes dangerously close to the line of Rule 11 — would have been filed absent the organizing efforts that Trader Joe’s employees have mounted (successfully) in multiple locations across the country.” In other words, the Court was saying that the real reason Trader Joe’s sued was to try and shut down the union, and that given the “extensive and ongoing legal battles of the Union’s organizing efforts at multiple stores, Trader Joe’s claim that it was genuinely concerned about the dilution of its brand resulting from [the Union’s] mugs and buttons cannot be taken seriously.” The Court went on to hold that no reasonable consumer would think that the union’s merch originated with Trader Joe’s — the central inquiry in a trademark infringement case. The Court also awarded the union its legal fees, noting in its decision that the case stood out “in terms of its lack of substantive merit . . . .” Ouch.

Famed restaurateur David Chang and his company, Momofuku, also recently lost a trademark battle they probably wish they hadn’t started. On the bright side for Chang and Momofuku, there was no lawsuit, and they weren’t unceremoniously kicked out of court like Trader Joe’s. However, they did have to issue an apology after sending a bunch of cease-and-desist letters to other Asian-American-owned businesses demanding that they cease and desist using the term “Chili Crunch.” (For those of you who mostly stick to milder foods, Momofuku Chili Crunch is a packaged “spicy-crunchy chili oil that adds a flash of heat and texture to your favorite dishes.”)

There was a lot of pushback on these letters from the recipients, who posted them to social media and shared them with mainstream media outlets, highlighting how Chang and Momofuku were trying to assert rights over a generic term frequently used in Asian and Asian-American gastronomic offerings. The companies (rightly) felt that Chang and Momofuku were trying to use their status and financial resources to attack other Asian-American-owned companies unjustifiably.

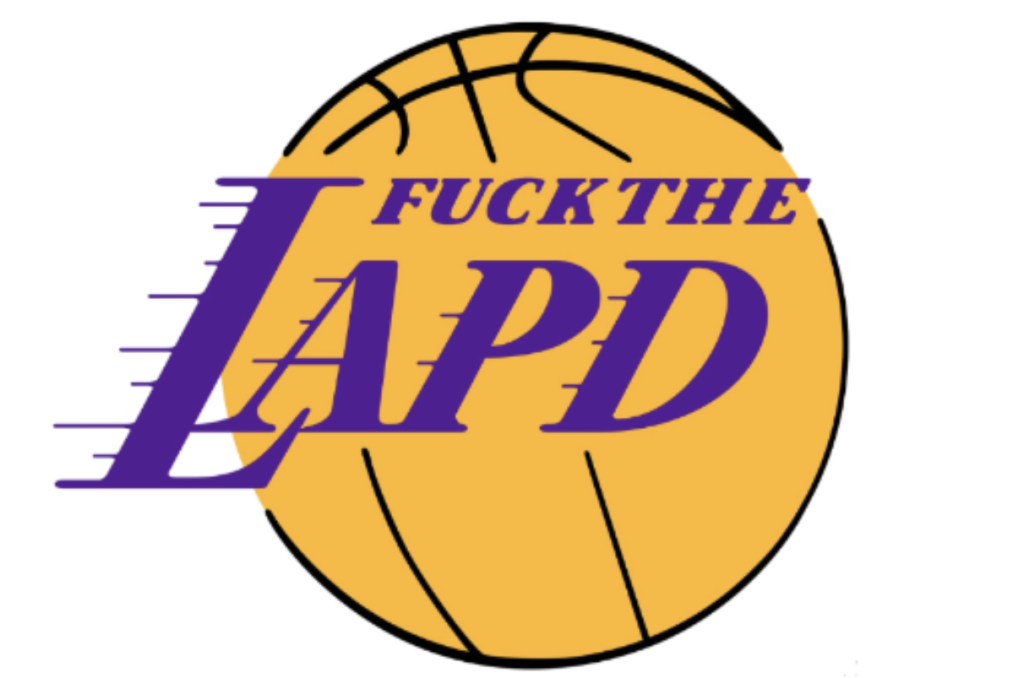

And then, there’s the case of the Los Angeles Police Foundation, a private group affiliated with the Los Angeles Police Department. It sent a cease and desist letter to a company selling tee shirts emblazoned with the words “Fuck the LAPD” on top of the Los Angeles Lakers logo.

In its letter, the LAPF asserted it is “one of two exclusive holders of intellectual property rights pertaining to trademarks, copyrights and other licensed indicia for (a) the Los Angeles Police Department Badge; (b) the Los Angeles Police Department Uniform; (c) the LAPD motto ‘To Protect and Serve’; and (d) the word ‘LAPD’ as an acronym/abbreviation for the Los Angeles Police Department . . .”

There are a lot of whiffs here for the LAPF. Strike one: Government agencies can’t get trademark protection for their names. Strike two: The LAPF isn’t the LAPD, so they have no basis for claiming infringement on something that isn’t even theirs. Strike three (it’s a doozy): Obviously, the logo on these shirts belongs to the Lakers, not the LAPF. Strike four: It’s fairly safe to assume that the shirt is meant as a parody and/or a political commentary, which are protected under the First Amendment.

Worth noting here is the tee shirt manufacturer’s carefully crafted response to the LAPF after receiving the cease-and-desist letter: “LOL, no.” That was literally the entirety of the tee shirt maker’s response—points for clarity, conciseness, and all-around humor.

What does this all mean? Well, if you send a cease and desist letter or file suit to protect a trademark you don’t actually have (LAPF), or if you’re trying to accomplish a goal that is not related to actually protecting your trademark (Trader Joe’s), you’re just going to be embarrassed. And while the Momofuku matter is more complicated and nuanced, it’s fair to say many companies use the term “Chili Crisp,” making Momofuku’s efforts to trademark it seem like the work of a bully.

So, the lesson here is that legal claims don’t exist in a vacuum. Examine the validity of your claims, but also consider the potential negative publicity and damage to your reputation before firing off cease-and-desists willy-nilly or filing suit. Even if you win in court, sometimes public opinion is the final judge, and no business wants to upset that judge.

June 11, 2024

The long-running dispute between wedding dress designer Hayley Paige Gutman and her former employer JLM Couture over ownership of the social media accounts she created and that bear her name is at last over.

On May 8, the District Court revised its earlier preliminary injunction and restored control of the @misshayleypaige Instagram, Pinterest and TikTok accounts to Gutman. In its decision, the Court held JLM couldn’t establish that the social media accounts belonged to JLM at their inception or that Gutman had transferred ownership to JLM.

In case you’re new to my analysis of the very public case (at least to Gutman’s 1 million-plus followers), I originally wrote about it here and, more recently, here.

How did the District Court reach a conclusion that is 180 degrees from its earlier decisions?

Well, in March 2024 the Second Circuit disagreed with the six-factor test the District Court created to determine ownership of the social media accounts and remanded the case back to the District Court with instructions to look at the accounts as normal property rather than through novel tests (a decision I heartily agreed with). After that, the District Court requested and received additional briefing on whether JLM could show that it either owned the accounts at the time they were created or that ownership was subsequently transferred to JLM, and that Gutman only had access to the social media accounts because she was a JLM employee.

In its analysis, the Court found:

- Gutman opened the Instagram account at the recommendation of a friend;

- She was at least partially motivated to create the accounts for personal use even if she saw them as potentially useful in promoting products manufactured by JLM;

- The Instagram was initially linked to her personal Facebook account;

- The Instagram account wasn’t linked to the JLM Facebook account until four years later; and

- The first five Instagram posts were clearly personal, as were early pins on Pinterest

According to the Court, taken together, these facts showed that Gutman created the accounts for personal use and not solely as a JLM employee, even if she did later use them to promote JLM products, allowed JLM employees access to them, and included links to JLM accounts.

Thus, since JLM couldn’t establish a valid claim to ownership of the social media accounts when they were created, it would have to show that the accounts were transferred to it. It was unable to do this for several reasons including the fact that Instagram’s terms of service prevent a user from transferring an account.

There were a few other interesting factors in the mix. For one, while Gutman’s contract with JLM included licensing her name to JLM for commercial purposes, she retained the right to use her name for non-commercial purposes. Thus, the Court found her use of @misshayleypaige as a handle on social media was not on its own a basis for finding that her social media accounts belong to JLM. And, as the Second Circuit found, the social media accounts themselves do not qualify as works for hire.

Gutman had also signed an employment manual with JLM in which she agreed that she would use her time during her workday only for employment-related activities; that her use of the Internet during that time was for job-related activities; and all intellectual properties she created belonged to JLM. The order modifying the preliminary injunction noted that even if Gutman’s posting on social media during working hours was a violation of JLM’s employment manual, it doesn’t mean that, despite JLM’s arguments, it was tantamount to her transferring her social media accounts to JLM. It does suggest, however, that JLM has a legitimate claim to the content Gutman posted on her social media accounts.

What’s really interesting here is that, in the end, the final decision in the District Court is opposite to the results reached by just about every other court that has looked at usage to determine ownership of a social media account. Will the Gutman decision reverberate throughout the growing number of legal disputes in this area, and give pause to companies who rely heavily on consumer relationships through the Instagram posts of highly visible employees and brand ambassadors?

What’s next? Well, not much. Shortly after the most recent decision from the District Court, Gutman and JLM resolved all matters in a settlement agreement that included Gutman paying JLM (well, its bankruptcy estate) $263,000. In exchange, Gutman was released from her non-compete agreement which would have continued for another 18 months or so.

May 29, 2024

If you’re into hip hop, you’re probably familiar with a photograph of rapper The Notorious B.I.G., a/k/a Biggie Smalls, looking contemplative behind designer shades with the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in the distance behind him. However, you might not know this well-known portrait has been the subject of litigation for the past five years and that litigation settled just before a trial was supposed to start earlier this year.

Photographer Chi Modu snapped the picture (the “Photo”) in 1996, originally for the cover of The Source hip hop monthly. However, after the magazine used another image, and Biggie was killed a year later, Modu began licensing the image to various companies, including Biggie’s heirs’ own marketing company. The Photo became famous and, after the destruction of the World Trade Center in 2001, what is now commonly called “iconic.”

There was no beef (do people still say that?) between Modu and Biggie’s heirs until 2018 when, according to an attorney for Chi Modu’s widow (the photographer himself passed away in 2021), Modu tried to negotiate increased licensing fees with Notorious B.I.G. LLC (“BIG”), which owns and controls the intellectual property rights of the late rapper’s estate.

Apparently, Modu and BIG weren’t able to reach an agreement because BIG brought suit against Modu and a maker of snowboards bearing the image, asserting claims for federal unfair competition and false advertising, trademark infringement, violation of state unfair competition law and violation of the right of publicity.

In a countersuit, Modu asserted his copyright in the Photo of Biggie preempted all of BIG’s claims. Modu argued that BIG’s claims were nothing more than an attempt to interfere with his right to reproduce and distribute the Photo, as permitted under Section 301 of the Copyright Act.

In December 2021, BIG sought a preliminary injunction barring Modu from selling merchandise including skateboards, shower curtains and NFTs incorporating the Photo, claiming these uses violated its exclusive control of Biggie’s right of publicity. (BIG had previously settled with the snowboard manufacturer.)

In June 2022, the Court granted the injunction in part, concluding that the sale of skateboards and shower curtains was not preempted by the Copyright Act as they did not involve the sale of the Photo itself but rather items featuring the Photo. In its order, it prohibited Modu’s estate from selling merchandise featuring the Photo or licensing the Photo for such use. However, the Court permitted Modu’s estate to continue selling reproductions of Modu’s photo as “posters, prints and Non-Fungible Tokens (‘NFTs’).” The Court found that the posters, prints and NFTs were “within the subject matter of the Copyright Act [as t]hey relate to the display and distribution of the copyrighted works themselves, without a connection to other merchandise or advertising.”

This decision follows a line of cases that distinguish between the exploitation of a copyright and the sale of products “offered for sale as more than simply a reproduction of the image.” In the former situation, a copyrighted work will take precedence over a right of publicity claim. In the latter, where the products feature something more than just the copyrighted work, a right of publicity claim is likely to prevail.

Not surprisingly, given the risks for both sides, the case settled just prior to the start of the trial. Although the contours of the settlement were not made public, presumably it allowed Modu’s estate to continue selling the Photo as posters of it remain available for purchase on the photographer’s website.