August 26, 2024

I spend a lot of time here nerding out about interesting cases and the many provocative types of legal conflict that continually arise. Keeping up with trending issues is an important part of what I do, and the latest disputes are more fascinating than ever.

But there’s another big part of my job that I talk about less that is just as captivating: Working with clients.

Why do I generally keep mum about this? Obviously, I can’t reveal any privileged client information. Also, litigation can be stressful, clients can sometimes have meltdowns and throw tantrums, and I’m not going to write about people’s bad moments even if they might be instructive for others. Finally, unlike reading and interpreting statutes and cases, working with clients isn’t something I learned in law school. It is a skill gradually acquired over years of practice and continual improvement. As a result, I (and most other lawyers I know) don’t really have an academic framework to organize and disseminate my expertise about working with clients.

But fear not: I’ve got a few things to share. Specifically, emotions, beliefs and behaviors I’ve seen that cause clients (and attorneys) needless stress and can make it harder to produce good results. Recognizing and anticipating these problem areas can help clients and attorneys have much better experiences as they navigate difficult litigation. (Also, it never hurts for me to put my thoughts down so that I can come back to them. Everybody wins!)

- The “It’s not fair!” syndrome. I think that a lot of people come to me feeling they’ve been treated in a way that is unfair and they expect “the law” to be on their side, and for lawyers and courts to make things right. In an ideal world that is exactly what would happen but, alas, as should be obvious to anyone over the age of 4, we don’t live in an ideal world. “The law” is made up of people. People with wildly differing beliefs and agendas. People who sometimes just plain get things wrong (that’s why we have appellate courts). Moreover, what’s fair to one person might not be fair to someone else. It’s important people put aside that powerful “it’s not fair!” feeling and focus instead on getting attainable, satisfactory results.

- “And another thing!” A lot of times people are determined to tell the opposite side in a dispute everything they’ve done wrong. But, in my experience, not every little thing matters. It is better to have one or two really good examples of why you’re right and/or the other side is wrong rather than throw everything but the kitchen sink at them. Doing so cuts down on needless back and forth and keeps the focus on those points that have power to change the situation. Plus, keeping some weapons in your arsenal in case you need them later is always a good idea.

- “Same thing, same result.” Often, when people come to me, they’ve already spent a lot of time going back and forth with their adversary and discussions have fallen into a predictable pattern. For example, your side keeps asking for information and the other side keeps ignoring these requests. And on and on. If you keep doing the same thing, you’ll probably keep getting the same result. That’s frustrating. If you want something different to happen, clients and attorneys need to be willing to try something different.

- “I’m not going to tell you.” If you’re a client, err on the side of telling your attorney too much, not too little. I cannot stress this enough. It’s much harder for me to help you solve a problem if I don’t have all the relevant information about the dispute, the opponent, and yourself. Anything can come up in a case, and the more unexpected it is, the more detrimental it can be — and the more stressful for my clients and myself. If I know about it, I can anticipate and plan for it.

- Finally, it’s important to draw lines (I’m not going to say, “in the sand!”). When you’re making demands of your adversary or laying out expected results, set boundaries and stick with them (of course, always be willing to adjust if you receive new information). If you don’t enforce a boundary, it can be a lot harder to get the other side to believe that this time you really mean it. When a client panics and suddenly wants to cave in on something their attorney doesn’t want to budge on, it causes tension between the two of you and jeopardizes your negotiating power going forward.

In all this, there’s a difference between understanding potential behaviors and eliminating them. But recognizing these patterns is definitely a productive first step toward ensuring a smoother, less stressful process for everyone involved in a litigation.

August 6, 2024

Everything should be clicking (as it were) for TikTok influencer Sydney Nicole Gifford. She has half a million followers who eat up her posts promoting home and fashion items from Amazon, propelling her to the kind of celebrity that garnered coverage in People for her pregnancy. But alas, Gifford is apparently a little too influential.

She claims fellow TikToker Alyssa Sheil is copying her posts and using Gifford’s visual style to promote the same products! And yes, Gifford is now suing Sheil, in a case that could shake up the world of social media influencers and potentially make it harder for influencers to create content without fear of accusations of copying.

According to the complaint, which was filed in District Court in Texas, Gifford “spends upwards of ten hours a day, seven days a week, researching unique products and services that may fit her brand identity, testing and assessing those products and services, styling photos and videos promoting such products and editing posts…” for social media. As a result, according to the complaint, “Sydney has become well-known for promoting certain goods from Amazon, including household goods, apparel, and accessories, through original photo and video works…”

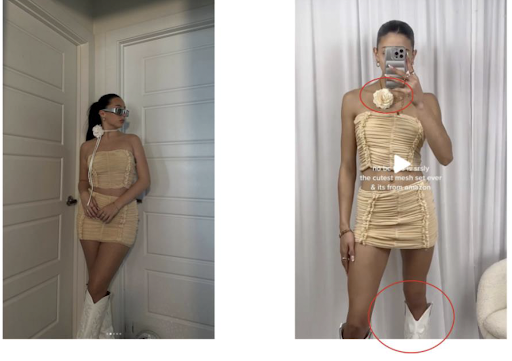

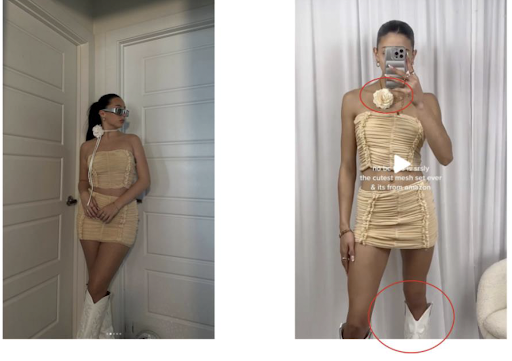

The lawsuit goes on to allege that defendant Sheil “replicated the neutral, beige, and cream aesthetic of [Gifford’s] brand identity, featured the same or substantially [the same] Amazon products promoted by [Gifford], and contained styling and textual captions replicating those of [Gifford’s] posts.” It says at least 40 of Sheil’s posts feature “identical styling, tone, camera angle and/or text,” to Sydney’s. Here’s a pretty obvious one, with Gifford on the left and Sheil on the right.

In the suit, Gifford is claiming, among other things, trade dress infringement, violation of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, copyright infringement (she has registered copyrights for some of her posts and videos), and unfair competition.

Does Gifford have a case? Here’s what I think:

- To prevail on the claim for infringement of her trade dress Gifford will have to establish, at a minimum, that consumers associate her “aesthetic” with her. That may be difficult because, at least to my eye, the style of Gifford’s posts doesn’t seem wildly different from a lot of other influencers. (I am so not her target audience and I’m doing my best not to dunk on her “aesthetic,” but I have to put “aesthetic” in quotes to convey my eyeroll.)

- The claim under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act is based on the fact that Sheil removed Gifford’s name or social media handle from posts. This is, shall we say, a novel argument given that the intent of the DMCA is to prevent people from circumventing digital rights management software. This is not that. At all.

- The copyright claim is going to raise a lot of questions about exactly how original these social media posts are and, as a result, how much protection under copyright law they are entitled to. Gifford and other social media influencers might find out that they don’t like the answer to this question.

- If Gifford is able to establish that consumers associate her “aesthetic” with her, she could win the battle… but lose the war because it might open her up to lawsuits by other influencers who claim that she copied their look.

Meanwhile, Sheil has asked the Court to dismiss Gifford’s case.

Thinking more broadly, a decision or decisions on the copyright claim could have implications for appropriation artists and others who closely copy another creator’s work. Which is one reason it will be fascinating to see how this plays out. And yes, I know I often end these posts saying something like that. Because it’s true! This case, as with so many IP lawsuits lately, especially those that involve AI, are all going where no court has gone before (or even imagined possible ten years ago). Every one of these potential decisions could have massive socioeconomic impact, with a real effect on how a lot of people earn a living and how the rest of us spend a lot (probably too much) of our time.

July 23, 2024

What do Baby Reindeer and Inventing Anna have in common? Sure, both are miniseries on Netflix. More interestingly, though, and more pertinent to this blog (since I’m not Roger Ebert), both are subjects of defamation lawsuits against the streaming giant. Nor is either action the first; I previously wrote about Linda Fairstein’s defamation lawsuit against Netflix over how she was portrayed in When They See Us. (That case settled in early June.)

These two current cases touch on slightly different aspects of defamation law. Inventing Anna tells the “based on a true story” of con artist Anna Sorokin, who posed as an heiress and defrauded a variety of New York institutions and individuals out of somewhere around $275,000. In addition to the protagonist, the series portrays several of her real life friends, including Rachel DeLoache Williams, the plaintiff in the lawsuit. Williams claims the series’ version of her is false and defamatory, especially in scenes showing her character abandoning a depressed Sorokin in Morocco and thus painting her as a “disloyal” and “dishonest” villain (instead of a victim who was defrauded by Sorokin to the tune of $62K).

Netflix sought to dismiss the lawsuit on grounds the allegedly defamatory statements were substantially true or were not defamatory. It argued that the show’s creators have a “literary license” to give their interpretation of events, and the characterization of Williams was an opinion, protected by the First Amendment from defamation claims.

The District Court did not see things this way and in March of this year it denied the motion finding that, at the very least, some portions of Netflix’s portrayal of Williams were false and capable of a defamatory interpretation. Specifically, the Court concluded that the issue of whether Sorokin was actually distraught in Morocco, or if that was an invention of the producers, is a question of fact that can be proven true or false. (To oversimplify things a bit, only false statements of fact can serve as a basis for a claim of defamation.) “Whether Sorokin was in a troubled state and Williams left her at that point can be proven true or false,” the judge wrote. The Court further concluded that showing the Williams character ditching a friend when she was depressed could indeed leave viewers with a negative view of the real Williams, and thus serve as the basis for a defamation claim. The case is proceeding.

In contrast, the Baby Reindeer case will focus on the question of whether the series’ portrayal of the character Martha is “of and concerning” a real-life person — the plaintiff, Fiona Harvey.

Baby Reindeer, which begins with the words “this is a true story,” was written by Richard Gadd, who also plays central character Donny Dunn, a not very funny wannabe comedian. It’s a fictionalized version of Gadd’s own life, and part of Donny’s saga involves being stalked by a character named Martha, which Gadd drew off a real experience.

According to the lawsuit, filed in early June, Harvey claims Gadd based Martha on her and cites several similarities between real life and fiction, including that both Martha and Harvey are Scottish lawyers of about the same age who live in London. The suit also claims that Harvey bears an “uncanny resemblance to ‘Martha’” (or at least the actress who plays the character), and “‘Martha’s’ accent, manner of speaking and cadence, is indistinguishable . . .” from Harvey’s.

Moreover, one plot point in Baby Reindeer (I’m trying to avoid spoilers as the show has a lot of twists and turns that would sound ridiculous if you haven’t watched it) mirrors something that Harvey tweeted at Gadd in 2014. Because of these similarities, according to the Complaint, within days of the series airing Internet sleuths determined she was the basis for Martha and began subjecting her to social media vitriol. “As a result of [Netflix’s] lies, malfeasance and utterly reckless misconduct, Harvey’s life had been ruined,” the suit states.

Harvey claims she was defamed by Netflix because Baby Reindeer portrays Martha as “a twice convicted criminal” who spent five years in prison for stalking people, as well as physically and sexually assaulting Donny. Harvey says she has never been convicted of any crime and did not attack the real-life Gadd.

The interesting issue here is that relevant case law doesn’t include, as a test, whether a fictional character can have their real-life basis be identified by Internet sleuths. Rather, the inquiry is generally whether a person who knows the plaintiff would reasonably conclude that the plaintiff was the fictional character, or in this case, whether friends and acquaintances of Harvey would link her with Martha. Netflix has been pretty adamant that it took steps to disguise the identity of the real Martha. Since there are numerous elements in the Martha character’s storyline that are clearly not connected to anything in Harvey’s real life, it seems very possible that the real Martha is someone other than Harvey. But the Internet has spoken, and that’s enough for Harvey to sue Netflix for $170 million.

We’ll have to see how all this pans out; it should make for pretty good legal viewing (although nowhere near as popular as Baby Reindeer itself, which is set to become Netflix’s most-streamed show ever).

One final note: Some people have asked me if I think there’s something wrong with Netflix’s legal vetting of shows. The answer: maybe, but let’s keep in mind that Netflix produces A LOT OF CONTENT, and obviously most of it isn’t causing trouble. That said, it seems like the streaming behemoth should start to exercise a bit more caution when greenlighting these series based on real stories, because there is a lot of money at stake, the Internet is rife with people looking to dig up the “truth,” and someone, somewhere, may very well cry defamation.