June 13, 2023

Well, that didn’t take long.

A pair of lawyers and their firm have very publicly and quite thoroughly embarrassed themselves by asking ChatGPT for case citations that turn out to have been made up by the trendy AI chatbot.

There are so many points of stupidity and laziness here: The global frenzy to adopt ChatGPT, the inability or failure of attorneys to understand new technology, one lawyer’s unthinking reliance on the work of a colleague, a law firm practicing in an area it is not equipped to handle … Let’s break it all down.

New York City law firm Levidow, Levidow & Oberman was working on what is, in most ways, an entirely unremarkable lawsuit: Roberto Mata v. Avianca. Their client — Roberto Mata — sued the airline Avianca claiming that, while on a 2019 flight from San Salvador to New York’s JFK airport, an airline employee failed to take sufficient care in operating a metal serving cart that hit Mata in the knee and seriously injured him.

In January 2023 Avianca moved to dismiss the case in the Southern District of New York Court, asserting the statute of limitations had expired. In March, Plaintiff’s counsel — Peter LoDuca — replied with an affidavit claiming otherwise. In his affidavit, LoDuca cited decisions from several cases including Varghese v. China Southern Airlines and Zicherman v. Korean Air Lines, both of which were supposedly decided by the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Avianca’s counsel quickly pointed out there was no evidence that those or other cases cited by Plaintiff’s counsel existed or, if they did exist, stood for the propositions that Plaintiff said they did.

The judge — P. Kevin Castel — was perplexed, and ordered LoDuca to file an affidavit attaching copies of the cases he cited. LoDuca complied — well, sort of. He submitted an affidavit that attached what he claimed were the official court decisions.

Defendant’s counsel again notified the Court that the cases did not exist or did not actually say what Plaintiff’s counsel had represented.

The judge, now rather angry, ordered LoDuca to show up in Court and explain exactly how he came to submit an affidavit — a sworn document — citing and attaching non-existent cases. In response, LoDuca submitted another affidavit saying that he had relied on Steven Schwartz, another attorney in his firm, to research and draft his affidavit. (By way of background, LoDuca and Schwartz have been practicing law for more than 30 years.)

And this is where the story goes from weird to bad. Really bad.

The reason LoDuca was appearing in Court instead of Schwartz is because Schwartz isn’t admitted to practice in federal court. He’s only admitted in state court where the case started out. To make matters worse, it turns out that despite the fact that Levidow, Levidow & Oberman were representing Mr. Mata in federal court, its lawyers didn’t have a subscription that allowed them to search federal cases.

Without this access to federal cases, Schwartz turned to what he thought was a new “super-search engine” (his words) he had heard about: ChatGPT. He typed questions, and the AI responded with what seemed to Schwartz to be genuine case citations, often peppered with friendly bot chat like “hope that helps!” What could possibly go wrong? A good deal. Because the cases ChatGPT provided Schwartz didn’t actually exist.

On June 8, 2023, the judge held a hearing to determine whether LoDuca, Schwartz, and their firm should be sanctioned.

At this hearing, LoDuca admitted he had neither read the cases cited nor made any legitimate effort to determine if they were real. He argued he had no reason not to rely on the citations Schwartz provided. Schwartz, embarrassed, said he had no reason to believe that ChatGPT wasn’t providing accurate information. Both admitted that, in hindsight, they should have been more skeptical. Counsel for Schwartz argued that lawyers are notoriously bad with technology (personally, I object to this characterization). Throughout the hearing, the packed courtroom gasped.

Cringe-inducing, to be sure. But looking deeper, there’s more to fault here than a tech-challenged attorney blindly relying on some “super search engine” to research case citations. The bigger problem is that, even after Avianca’s lawyers pointed out they couldn’t find any evidence that the cases existed or said what Plaintiff’s lawyer said they said, Plaintiff’s attorneys — LoDuca and Schwartz — persisted in trying to establish that the “cases” they relied on were real despite possessing absolutely no evidence for it. Even after Schwartz couldn’t find the cases through a Google search, neither he nor LoDuca checked the publicly available court records to see if the cases were real. Moreover, they seem to have disregarded some pretty clear signs that the “cases” were, at best, problematic. For example, one case begins as a wrongful death case against an airline and, a paragraph or two later, magically transforms into someone suing because he was inconvenienced when a flight was canceled.

Should the duo and their firm be sanctioned? In general, the standard for sanctions is whether those involved acted in bad faith. Everyone here insisted that their conduct did not meet this standard. Rather, they claimed they were simply mistaken in not knowing how ChatGPT worked or that it couldn’t be trusted.

The judge certainly didn’t seem to see things that way. He was appalled that Schwartz and DoLuca didn’t try to verify (or, apparently, even read) the “cases” they cited. In court, the judge read aloud a few lines from one of the fake opinions, pointing out the text was “legal gibberish.” In addition, while LoDuca, Schwartz and their firm might not have been trying to lie to the court, it’s hard to believe that they fulfilled their obligation to make “an inquiry reasonable under the circumstances,” which is what is required under one of the rules applicable here.

The judge reserved a decision on sanctions, so stay tuned.

May 31, 2023

We’ll keep this brief as the U.S. Supreme Court’s May 18 decision in Goldsmith v. Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. has already been examined by many others. For example, here, here and here. Also, there will be much more to come as people have time to digest the Court’s ruling and the dissent.

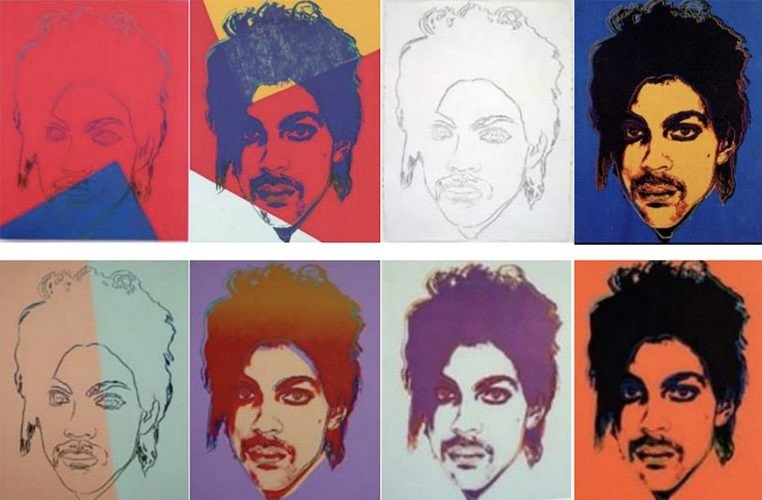

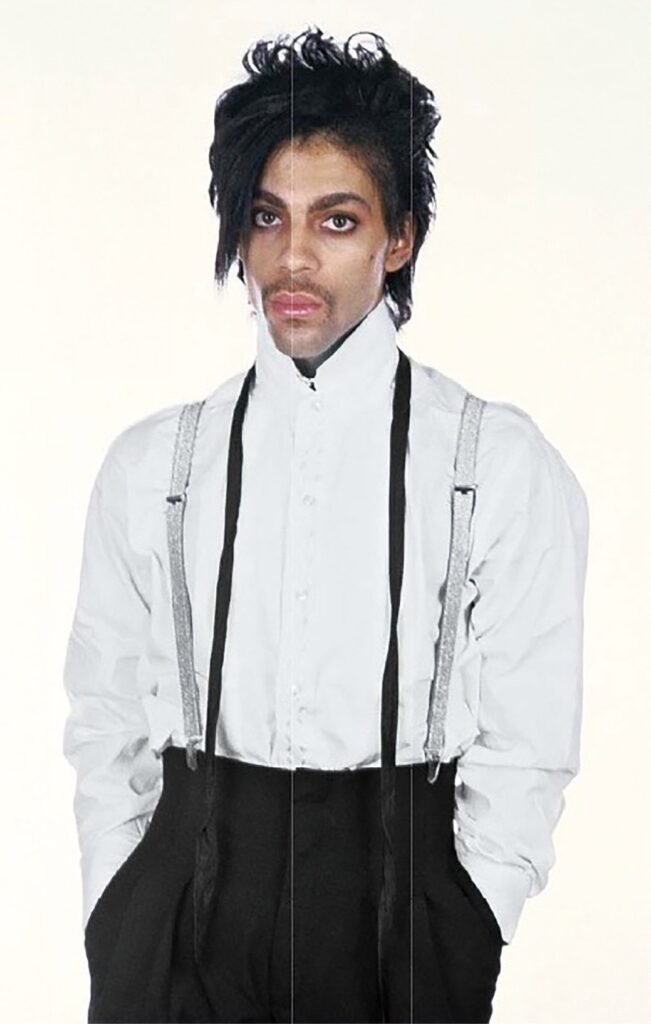

The majority decision, written by Justice Sotomayor, held that Andy Warhol’s artwork Orange Prince, based on a photograph by Lynn Goldsmith and used by Condé Nast on the cover of a 2016 special edition magazine celebrating Prince’s life, was not sufficiently transformative. The Court concluded that the first fair use factor — the “purpose and character” of the second work — favored Goldsmith and not the Foundation. The Court rested its decision largely on the fact that Goldsmith’s photo and Orange Prince both could have served as the magazine cover and, significantly, Condé Nast chose to use Orange Prince as a substitute for Goldsmith’s photo on its magazine. One key point: the creation of Orange Prince went beyond the terms of the publisher’s original 1984 license for Goldsmith’s photo and Goldsmith wasn’t credited as the photographer when Condé Nast used the image in 2016.

By focusing on the fact that Warhol’s adaptation competed commercially with Goldsmith’s original for this specific application, the Court largely avoided having to answer the question of to what extent Warhol’s image visually transformed Goldsmith’s image. This is probably a good thing as judges should not moonlight as art critics. This decision allowed the Court to preserve the right of copyright holders to make derivative works, which would have likely been threatened by a ruling for the Foundation.

However, not everyone on the Court agreed. Justice Kagan wrote a blistering dissent in which she accused the majority of ignoring the extent to which Warhol was a transformative artist.

This focus on Warhol’s overall legacy, however, has its limits as it is not helpful when the next case deals with an artist who is far less famous or has a much less immediately identifiable style than Warhol (which is pretty much everyone). Moreover, Justice Kagan’s hypothesis that Condé Nast selected Orange Prince over the Goldsmith photo because the editors preferred the aesthetics of the Orange Prince ignores one obvious possibility — Conde Nast went with the Warholized image because they thought it would sell more copies of the magazine. The dissent’s failure to recognize Warhol’s unique level of fame and its commercial impact is a pretty big blind spot.

Putting all of that aside, as noted above, the majority’s opinion has the advantage of shifting at least some of the analysis away from having a judge (or a jury) determining the transformativeness of an artwork. However, the majority’s decision does have problems. For starters, it collapses or combines the first fair use factor (“the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes”) and the fourth fair use factor (“the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work”). Moreover, the idea that Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photo is fair use if the image hangs in a museum, but not if it’s on the cover of a magazine is odd. What would have happened if Orange Prince was on the cover of an issue of Vanity Fair that looked at celebrity culture or a catalog of a museum exhibition? Is the analysis different and do artists (and lawyers) now have to make judgments for each particular use? That would seem to be a bad thing. We shall see.

May 16, 2023

Taking a break from our focus on trademark and copyright lawsuits, let’s look at a current high-profile case raising an issue that impacts all sorts of litigation — the obligation to preserve documents, including ephemeral messaging like online chats.

Why does this matter? In litigation, the discovery process requires each side to preserve documents and other materials relevant to the lawsuit so they can be provided to the opposing side. This obligation is triggered as soon as a party knows that litigation might happen. (We’re simplifying, but that’s the gist.) When a litigation starts, companies will often put in place a “litigation hold,” alerting employees who might have relevant information that they have to preserve documents. A litigation hold will also generally involve overriding the processes that might ordinarily delete emails, documents, etc.

Failure to preserve or provide these materials can have serious consequences. In extreme cases, a court will dismiss a plaintiff’s case or find against a defendant that has failed to comply with its obligation to preserve documents.

That brings us to a current lawsuit against Google brought by consumers, state attorneys general and app developers, claiming the omnipresent tech giant illegally monopolized the market for Android apps. During discovery, the plaintiffs noticed that Google hadn’t produced its employees’ instant messages related to the case. When the plaintiffs raised this issue, Google made some surprising revelations — its internal chats are generally deleted after 24 hours and it hadn’t suspended this automatic deletion for employees subject to the litigation hold in this case. Instead, Google allowed them to decide whether or not to preserve their instant messages.

Google is certainly no stranger to litigation holds. The company specifically trains employees to “communicate with care” because of the possibility of communications becoming public through discovery, and automatically preserves company emails that are subject to a litigation hold. And obviously, one of the world’s most powerful tech companies was perfectly capable of turning off auto-delete for the specific employees involved. Instead, Google simply told them not to discuss topics related to the litigation on chat but, if they did, to retain those specific chats if they felt the content was relevant. It was all self-policed: Google didn’t do anything to require employees to save chats or ever check to see if employees were complying. Only after the plaintiffs raised the issue during discovery did Google change its settings so that chats were saved by default.

In its attempt at explanation, Google argued that employees’ chats were mostly used for social purposes, even though the record (and common knowledge) clearly indicates that workplace chats are constantly used for substantive business purposes which, in this case, included matters relevant to the antitrust litigation.

The court, understandably, was not impressed by this argument. It concluded that as a result of Google’s lax policies, employees failed to save chats related to this litigation. The court also found that since employees were aware chats weren’t being preserved, they freely engaged in “off the record” convos related to the case knowing they couldn’t be used in court. The judge specifically rebuked Google for allowing employees to decide which chats could be used as evidence, pointing out that staffers probably wouldn’t be capable of making those judgments.

Ultimately, the court was very concerned about the intentionality of Google’s conduct, concluding that Google “intended to subvert the discovery process, and that Chat evidence was ‘lost with the intent to prevent its use in litigation’ and ‘with the intent to deprive another party of the information’s use in the litigation.’” The judge made it clear he believed Google was trying to destroy pertinent evidence, and directed Google to pay plaintiffs’ fees in connection with bringing this motion. The court also said that it would set a non-monetary sanction against Google at the end of discovery when the court is in a position to better determine what has been lost.

Overall lesson here: if you’re in a litigation, immediately start preserving all documents related to the case, including chats, just as you would to any other type of messages.